Umrao Jaan wasn’t made for the box office—it was made for the soul, says Muzaffar Ali

Muzaffar Ali reflects on the 4K re-release of his 1981 classic—on poetry, silence, and making a film for those who feel, not just watch.

Some films do not just tell a story—they leave behind a fragrance, a silence, a world. Umrao Jaan, first released in 1981, has always felt like one of those rare films. Watching it again, after so many years, I felt it asked something of me: to slow down, to listen, to feel. It wasn’t just a period piece; it was a lament. A cinematic elegy for a way of life that had quietly receded into history—the tehzeeb of Lucknow, the cadence of Urdu, the rituals of silence and suggestion.

Now, forty-four years later, Umrao Jaan returns to the big screen, digitally restored in 4K by the National Film Archive of India and NFDC, and released theatrically on June 27, 2025. But this doesn’t feel like just a restoration of images. It feels like a revival of sensibilities—of grace, restraint, sorrow, and language. Watching it is to step back into a world where poetry lived in every pause, where desire wore the mask of decorum.

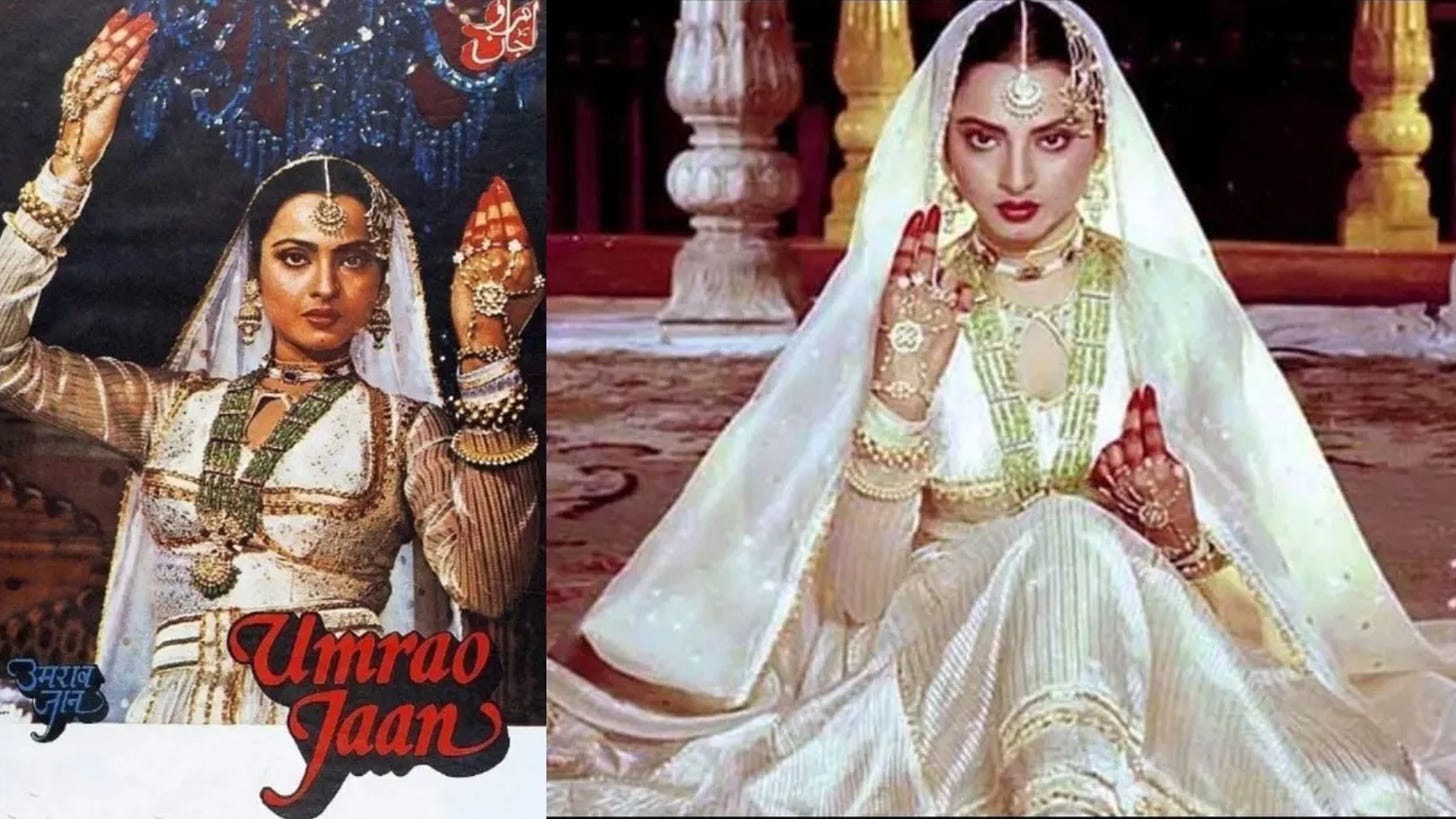

Rekha as Umrao Jaan was re-released in theaters on June 27, 2025, after being digitally restored.

I spoke to filmmaker Muzaffar Ali over the phone about the re-release. “This wasn’t a film meant for the box-office,” he said. “It was made for those who have patience—for those who seek meaning beyond spectacle.” He knows the film’s stillness may seem unfamiliar to younger viewers. But that, he believes, is precisely its power. “It invites reflection. And that is something we need more of today.”

Ali had always imagined the film as an act of cultural memory. Not a sweeping historical drama, but a tender, melancholic retrieval of a world he feared was vanishing. “I made this film just in time,” he said. “Many of the things you see on screen had already disappeared—the way women sat, the way people spoke, the spaces they inhabited.”

Some of those spaces were real—filmed in the narrow lanes and grand courtyards of Lucknow, Faizabad, and Malihabad, places Ali knew like his own breath. The rest, like the unforgettable kotha where Umrao performs, were rebuilt with old wood, vintage mirrors, and antique doors. The atmosphere was built not just through set design, but through shadows, silences, and a kind of emotional architecture.

But all of it would have meant little without Rekha. From the start, Ali knew she was his Umrao. Not because of stardom, but because of the stillness she carried. “We didn’t plan each scene like a formula,” he said. “We just imagined how a woman like her might feel, how she might respond.” Rekha responded not with artifice, but absorption. She became Umrao.

Watching her again in this restored version, I was struck by how alive her performance still feels—how her eyes held back more than they revealed, how her movements carried the ache of someone forever out of place. She is a woman abducted as a child, trained as a courtesan, transformed into a poet—and yet, never allowed to truly belong.

Umrao Jaan restored in 4K version by NFDC and NFAI

Every person who enters Umrao’s life leaves a trace. Shaukat Kaifi’s Khanam Jaan, regal and steely, initiates her into the codes of the courtesan. Dina Pathak’s Bua Husaini offers her fleeting maternal warmth. Jagirdar’s Maulvi grounds her in quiet spirituality. Naseeruddin Shah’s Gauhar Mirza awakens her sensuality, while Farooq Sheikh’s Nawab Sultan offers love—though not permanence. Raj Babbar’s Faiz Ali becomes her reckless escape. And in one of the film’s most devastating moments, Farrukh Jafar as Umrao’s birth mother reappears—only to retreat again. “That moment tore into people,” Ali said. “It left a scar.”

If Rekha carried the ache, Khayyam’s music carried its breath. The songs weren’t decorative; they were narrative. Each ghazal, each mujra, felt like a diary entry in Umrao’s inner life. “I wanted the lyrics to carry the history,” Ali said. “The music had to express the mood of a vanishing culture.” Shahryar’s poetry, and Asha Bhosle’s fragile, soaring voice, gave that mood its soul.

The mujras were choreographed by two legends: Gopi Krishna and Kumudini Lakhia who brought different textures to Rekha’s movements. Despite no formal dance training, Rekha had what Ali called bhav—that elusive blend of grace, poise, and emotional presence. It wasn’t about footwork. It was about how she held sorrow in stillness.

Umrao Jaan was made on a modest budget. It went on to win four National Awards—for Rekha’s performance, Khayyam’s music, Asha Bhosle’s playback singing, and Manzoor’s art direction. But its biggest success wasn’t on paper. It was in how it told the story of a woman we rarely see—misunderstood, misremembered—and gave her her due.

The film still isn’t available on any streaming platform. Which means this theatrical release is more than a rewatch—it’s a rare opportunity. “If this helps young people experience something real, something rooted,” Ali said, “then the film has done its job again.”

As our conversation ended, I kept thinking of Umrao—alone in her room, scribbling verses that may never be read. But she writes anyway. Because she must. Because she has to hold on to something. And maybe that’s what Umrao Jaan does too. It doesn’t scream to be heard. It lingers, gently. Like the sound of anklets fading into silence.

Its really a wonder, that a youngster like you are putting an immence view on a historic and a traditional character "Umrao Jaan"

I appreciate your vision and the way you carried it very carefully ...

Keep it up..